DAFOE: “Better editor of the Free Press than Prime Minister of Canada”

John Wesley Dafoe was brought to Manitoba in 1901 by Sir Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior at the time, to edit his Manitoba Free Press, later to become the Winnipeg Free Press in 1934. His hiring was at a time when the west was being opened up, at the behest of the minister. And by the 1930s Dafoe had cut a huge swath through Canadian politics – familiar with every face of power.

John Wesley Dafoe was brought to Manitoba in 1901 by Sir Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior at the time, to edit his Manitoba Free Press, later to become the Winnipeg Free Press in 1934. His hiring was at a time when the west was being opened up, at the behest of the minister. And by the 1930s Dafoe had cut a huge swath through Canadian politics – familiar with every face of power.

He was a strong advocate of national status for Canada and was a noted figure at every Empire conference after 1909. He advanced the idea of “commonwealth” displacing centralized empire. He saw hope in a league of nations. These bordered on treason when Dafoe raised them in the 1920s. He liked to think their advocacy was the great work of his life. The Statute of Westminster in 1931 creating a Commonwealth of equal nations was precisely the formula Dafoe had espoused for nearly a decade.

His profile was such that in 1942 Fortune Magazine wrote that Winnipeg’s “body was built around wheat. Its mind was built around Dafoe.” Headline on the article called him “ The Greatest Man in Canada.”

“Today at 76, John Wesley Dafoe, editor of the Winnipeg Free Press, is the most representative living Canadian and, as the record abundantly proves, the wisest. He is more than that. The record will hardly show a journalist writing in English who saw so early the drift toward a new synthesis or new ruin; who struggled so long for a discarded idea and has been so richly vindicated by events.” The author of this view was Vancouver journalist Bruce Hutchison.

The synthesis, the idea, he was talking about was, of course, free trade; and the ruin was Hitler and World War II. What made the man great? Simply courage, consistency and integrity.

Dafoe editorial principles extended beyond the wishes of his employer. Dafoe did not back down when his Free Press editorial supported free trade, and Sifton, his cabinet member owner, opposed it. Dafoe very clearly understood what nationhood would mean for Canada at a time when opposing Britain on anything was seen as almost treasonable. And he put principle ahead of profit by opposing Hitler and appeasement even as the circulation of his paper fell.

He carried his service into the community. As University of Manitoba Chancellor in the grim 1930s, he was no ornament on the Board of Governors. His efforts were deemed to have contributed with restoring the university from the tragic financial disaster, which overtook it in 1932.

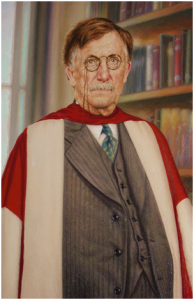

Contemporaries described him as a somewhat rumpled soul in the newsroom of the Free Press. Photographs at the time show him wearing pince-nez glasses with a long black string hanging from the left lens. His hair was usually awry at work, his suit thick and crumpled. He was a tough-thinking, detail man. He could be irascible. And aloof. He refused a knighthood, claiming with pride that he shoveled his own snow at his home on Wellington Crescent and tended his own furnace. His grandson, Christopher Dafoe, speaking at an induction ceremony memorializing grandfather’s citing for entry to the Citizens Hall of Fame in 2002, said he had a small ego and wasn’t much impressed with honors. Besides refusing the knighthood, he turned down the offer of a seat in the Senate and a consular position in Washington. When in the 1926, he was approached to run for the Liberals in the federal election. He reasoned that as a candidate he would have to give up his editorship. His conclusions: “ I think I would rather be editor of the Free Press than Prime Minister of Canada.”

Dafoe’s beginnings were in rural Ontario. He was born in Combermere in the Ottawa Valley on March 8, 1866 to homesteading “rock farmers” Calvin and Mary Dafoe. Farm poverty forced Calvin to lumber jacking. At 13, young Dafoe was sent to school in Arnprior, return to teach at 15 at Bark Lake, 20km from the homestead. In 1883, Dafoe put the classroom behind him and became a cub reporter at the Montreal Star, under editor Hugh Graham. Within a year he was flung into the political environment as parliamentary correspondent for the Star. He moved from the Montreal Star in 1885 to become editor of the Ottawa Evening Star, within six months had been snapped up to take a job as a reporter at the then Manitoba Free Press. Dafoe married Alice Parmalee in 1890 after a seven-year friendship dating from his early days in Ottawa. They had seven children. Dafoe so liked the prairies he encouraged his family to up-stakes in Combermere and move west. They settled in Killarney. But Dafoe had not found his slot. He was wooed away to the Montreal Herald for two years. But when the Herald went bankrupt and the fill-in jobs didn’t appeal, the couple returned to Winnipeg with a good contract from Sifton that gave him full editorial control of the newspaper, which included unqualified support for free trade (contrary to his owner’s position).

1866 to homesteading “rock farmers” Calvin and Mary Dafoe. Farm poverty forced Calvin to lumber jacking. At 13, young Dafoe was sent to school in Arnprior, return to teach at 15 at Bark Lake, 20km from the homestead. In 1883, Dafoe put the classroom behind him and became a cub reporter at the Montreal Star, under editor Hugh Graham. Within a year he was flung into the political environment as parliamentary correspondent for the Star. He moved from the Montreal Star in 1885 to become editor of the Ottawa Evening Star, within six months had been snapped up to take a job as a reporter at the then Manitoba Free Press. Dafoe married Alice Parmalee in 1890 after a seven-year friendship dating from his early days in Ottawa. They had seven children. Dafoe so liked the prairies he encouraged his family to up-stakes in Combermere and move west. They settled in Killarney. But Dafoe had not found his slot. He was wooed away to the Montreal Herald for two years. But when the Herald went bankrupt and the fill-in jobs didn’t appeal, the couple returned to Winnipeg with a good contract from Sifton that gave him full editorial control of the newspaper, which included unqualified support for free trade (contrary to his owner’s position).

Dafoe was at the Peace Conference in Paris in 1919, when the violence of the Winnipeg Strike burst onto the streets. But he made his position felt editorially and it didn’t favor big unionism. He was perceived as siding with the community’s elite and his reference to immigrant “aliens” painted him with a streak of intolerance not uncharacteristic of the successful British stock, which lived in comparative privilege.

Dafoe died at 77 on Jan. 10, 1944, having filled the editor’s chair for 44 years. He made the paper one of the most respected in the world for his positions on the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations, the British Commonwealth’s formation, the shame of “peace with honor”, the travesties of Japan in China and its much later attack on Pearl Harbor, the horrors of Hitler and Mussolini and Canada’s role in processing the world war. Tributes from around the world filled the paper.

Prime Minister McKenzie King said on that day, “Mr. Dafoe contributed to shaping as well as writing the history of our country. He was a recognized authority on international constitutional and political questions. On public affairs his views and opinions were widely sought. To leaders in public life he was a wise counselor and helpful friend.